As classrooms across the country become increasingly diverse, educators have mixed opinions about the best ways to address the subject of race and racism. Much of the concern centers on how old children should be when they begin learning about issues of race.

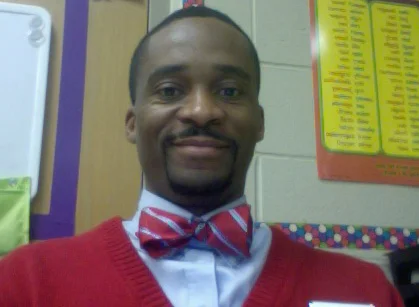

Terry Husband, associate professor in the Illinois State University College of Education, is a strong advocate for addressing the subject of race when children are young. “I believe children as early as age 3 or 4 begin to crystallize their notions about what men do, what women do, what white people do, what black people do, what Hispanic people do, etc.,” he said. “But the question is, how do we teach young children in particular about issues of race in ways that are both developmentally appropriate for their age level as well as critical?”

Teaching young children about Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks without discussing slavery and the Klu Klux Klan would be giving them an inaccurate view of history. —Terry Husband

Husband has believed that for years there has been a romanticized version of race and the fallacy is “that race isn’t something in society that is conflicting, that race isn’t something that is socially constructive, and that race doesn’t exist.” He believes this misconception is more harmful than productive, and when these young children become fifth-, sixth-, seventh-, or even eighth-graders and see the world, they are very disillusioned. “I argue that on a lot of levels, what you don’t teach is as equally instructive or powerful as what you do teach—especially as it relates to issues of diversity,” he said.

Before Husband began teaching at Illinois State University, he taught first grade at an urban school in Columbus, Ohio. He introduced his young class to racism using drama.

He developed 10 lessons on African-American history that were organized chronologically and included the beginnings of slavery, the anti-slavery and abolitionist movement, and desegregation and freedom. “From my vantage point, teaching young children about Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks without discussing slavery and the Klu Klux Klan would be giving them an inaccurate view of history,” explained Husband.

During one of the lessons in his classroom, the students read and discussed select passages from Now Let Me Fly: The Story of a Slave Familyby Dolores Johnson and If You Lived Where There was Slavery in America by Anne Kamme. Husband then divided the students into two groups and asked them to imagine they were either slaves working on a cotton plantation or slave masters who forced the slaves to pick cotton.

“What becomes evident in this example is that drama provided a space within the lesson where students began to move from superficial notions of race to a better understanding of the competing interests between the slaves and slave masters during this period of time in history,” said Husband. He felt this lesson helped his students to better empathize with the emotions associated with racial injustice.

Husband noted some very significant findings from the study. Students moved beyond the notion of race and began to think of it outside the idea of politics and as something more rooted in society. “There is so much attached to race—it’s socially constructed and it’s historically constructed,” said Husband. “It’s not just I’m black, you’re white, but with race there is this awareness of the historical nuances or baggage that come along with it.”

Husband noted that ideas of racism are deeply subjective, vary from person to person, and are not necessarily based on one’s race. “During the lesson on the abolitionist movement, the students began to wrestle with the idea that some whites worked toward helping slaves achieve freedom while some slaves refused to escape from the plantation,” he said. “In this dramatic interaction, students began to construct and communicate notions of race as a largely complicated concept.”

Husband also discovered that race is deeply systemic. He used children’s literature books to look at some of the legislation about integration. The class read about Ruby Bridges’ experiences being the first African-American girl to integrate into the school system in New Orleans. “It was really meaningful for the children to see the pictures of Ruby walking to school being escorted by the U.S. Marshals,” said Husband. “The students were able to see racism is built into our institutions in society and if you want to counter-resist this, you have to do it at the individual and the institutional level–they both work simultaneously.”

The dramatic lessons allowed students to communicate and express an understanding of race and racism in a constructive, non-traditional way. Moving forward, Husband believes that young children need to be made aware of racism so as they get older they can build on that awareness. “The process needs to begin early so when they are in high school and college, there isn’t a large level of cultural dissonance,” he said. He also believes this awareness will help them later in life. “Eventually, when they are in a position in society to be one of the gatekeepers, then they can be sensitive to racial issues,” said Husband.