"Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.”

1940: Miller Park's whites-only beach.

That famous quote attributed to Edmund Burke, a one-time orator, political theorist and British member of parliament, is behind a new effort at Bloomington's oldest park.

The Illinois State Historical Society is putting up a marker to stand as a permanent reminder of the history of racial segregation at Bloomington’s Miller Park.

From 1908 and into the early 1950s when the beach was closed for a time, the swimming area at Miller Park was divided by a well-maintained section with a lifeguard and an unkempt, unguarded section labeled “Blacks Only.”

The Community Has A Secret

Mark Wyman, a retired Illinois State University distinguished emeritus history professor, said when the beach was reopened in 1957, there were no references to the decades of segregation.

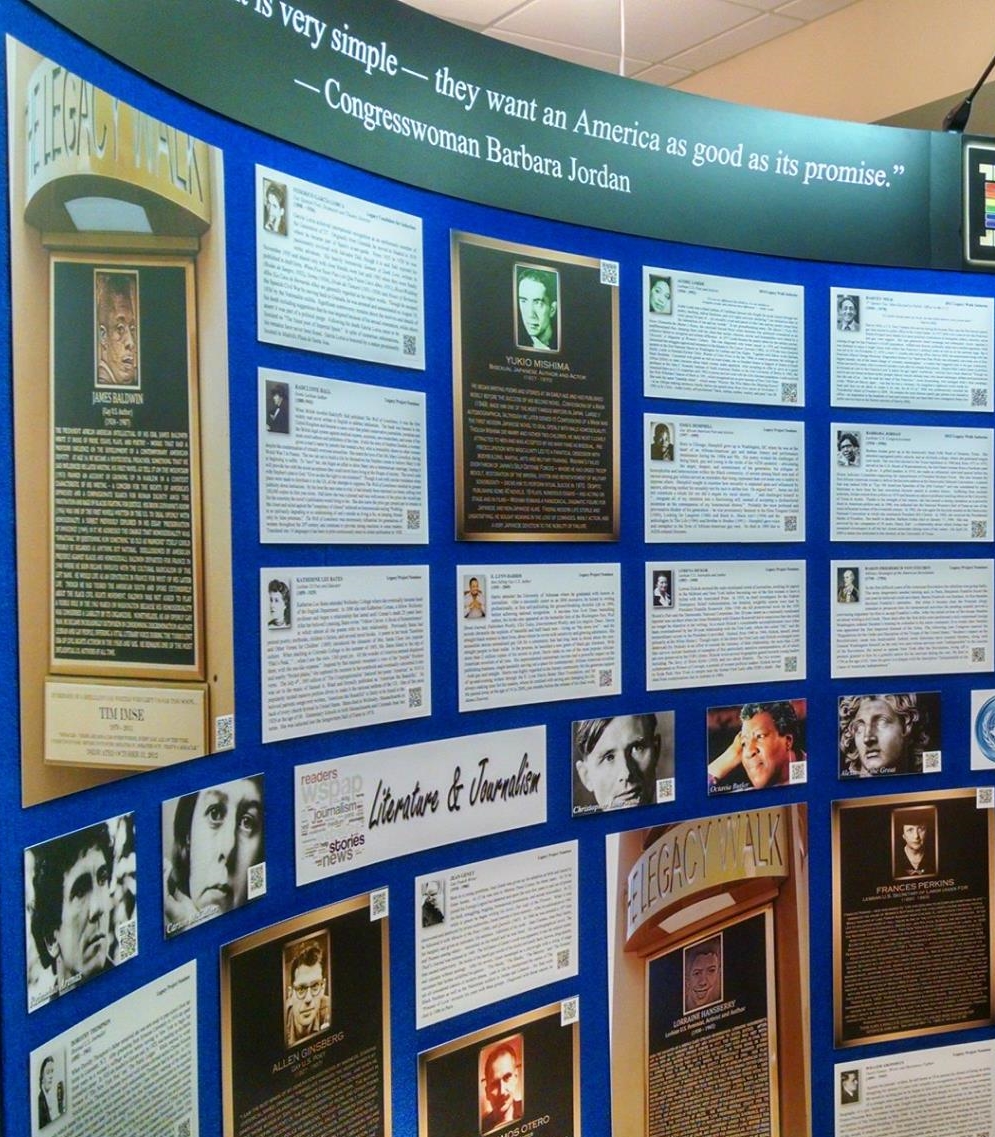

The marker the McLean County League of Women Voters erected in Franklin Park in 2005 to recognize the local resident who was the first woman elected to the Illinois Senate.

Credit Illinois State Historical Society

"I saw the secret really develop then because in all of the editorials about reopening and in the speeches by the mayor, no mention that it used to be segregated until it closed in 1953," said Wyman, who along with historian Jack Muirhead researched the history and interviewed residents about what they knew about the separate and not-so-equal policies at Miller Park lake.

“People were not aware of that. ‘Did we ever have segregation here?’ they asked longtime residents. The replies were all the same, ‘No, too far north. No, never heard of it.’ Wyman said he and Muirhead heard the same response many times. "That’s when I realized this community has a secret."

The NAACP is supporting the project along with the McLean County Museum of History and the Not In Our Town (NIOT) coalition. Camille Taylor of NIOT said history has a way of repeating itself, so the marker is an important recognition of this community's ability to discriminate.

"Our mission is to stop hate, address bullying and to make a safe, more inclusive community for all so the things that Mark describes would certainly be under that mission in terms of sharing the history of segregation and where we are now as a community," Taylor said.

Taylor was involved in The Bloomington-Normal Black History Project, formed in 1982 to document the local history of the local black community with a collection that now contains photographs, portraits, booklets, articles, and artifacts.

The former Unit 5 counselor used those artifacts and documents for presentations during Black History Month at area schools. She said students could not understand why blacks were not allowed to swim in the same section of Miller Park lake.

"When I talked about Miller Park and a little girl named Phyllis Hogan who had to swim in the segregated part of the lake that had lots of debris and she got caught up in it and drown and some of the children were the same age as this little girl ... they couldn't believe it. They would ask, 'Why would they make those people do that?'" she said.

"That's when I realized this community has a secret."

Taylor said the students hearing those presentations in the 1980s and 1990s had no idea about this kind of treatment of blacks in their own community.

"Their eyes opened as big as saucers when they would hear things like the cheerleaders at Bloomington High School, going downtown to the square after a game and they wouldn't be served if a black cheerleader was with them, so all the cheerleaders got up and left," Taylor said about how the children responded to her accounts of discrimination.

She said the historic marker will be permanent and do more good to educate people and bring awareness than what she was able to accomplish through her school visits.

Plenty of Support

Wyman said he has encountered no opposition from city leaders including Alderman Karen Schmidt whose ward includes Miller Park. He was never worried about raising the estimated $4,000 to erect the marker and he says once he began talking about it, the money flowed in.

"Right away when I would mention it in talking to groups around town about our segregation past people would come out and say, 'I want to donate.'" He said several individuals who read about it in the McLean County Historical Society newsletter contacted us and offered donations.

The marker will measure 44 by 51 inches. There has not been an Illinois State Historical Society marker erected in the Bloomington-Normal area since 2005. Twelve years ago, the McLean County League of Women Voters sponsored a marker on the east side of Franklin Park honoring the life and career of pioneering lawmaker and community leader Florence Fifer Bohrer.

Wyman said plans are to put up the marker sometime this spring.

It includes 16 lines of text including a final line that reads, “Today, Miller Park—like all city facilities—is open to all.”